- On March 9, Mohammad Arif, a 35-year-old man from Mandkha, Uttar Pradesh, was booked under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, for “illegally” keeping and nursing an injured Sarus crane (Grus Antigone) he found in his village.

- The Sarus crane is usually found in wetlands and is the state bird of Uttar Pradesh. Standing at 152-156 centimetres, it is the world’s tallest flying bird.

Wildlife Protection Act

- The Wildlife Protection Act came into force on September 9, 1972

- The act aims to “provide for the protection” of wild animals, birds and plants to ensure the “ecological and environmental security of the country.”

- It aims to conserve protected species in two main ways: firstly, by prohibiting their hunting and secondly by protecting their habitat through the creation and regulation of sanctuaries, national parks, reserves, etc.

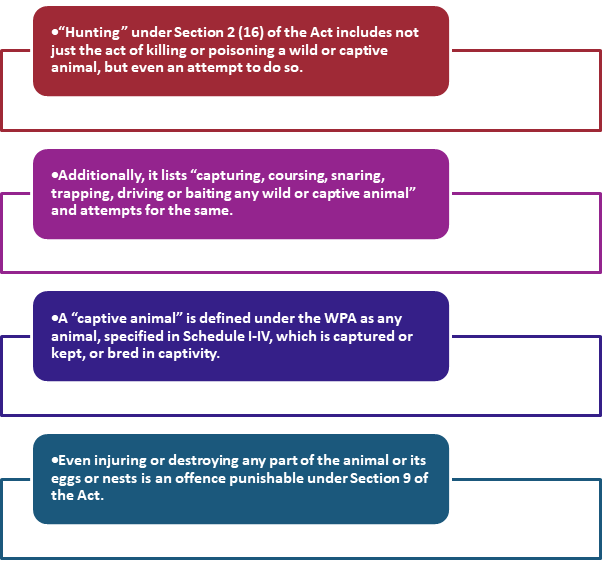

- The Act prohibits capturing or hunting any species of animals listed under Schedules I-IV

Hunting under the Act

What Are The Schedules Listed In The Act?

The Act protects wild and captive animals or birds which belong to a species listed under Schedules I-IV.

Schedule I & Schedule II – “Strictly Protected Species”

- No wild or captive animal or any products derived from them, like their fur, skin, tusks, etc., can be possessed without an ownership certificate

- Animals such as the Black Buck, Black-Necked Crane, Hooded Crane, Siberian White Crane, Wild Yak, and the Andaman Wild Pig fall under Schedule I.

- Whereas, the common Langur, chameleon, and King Cobra fall under Schedule II.

Schedule III & Schedule IV- Protected but the penalties are lower

- Schedule III includes Chital, wild pigs, Hyaena, and the Nilgai.

- The Sarus crane falls under Schedule IV of the Act.

- Species mentioned under Schedules III and IV of the Wildlife carries prohibition on dealings in trophy and animal articles without a license, purchase of animals by a licensee, and restriction on transportation of wildlife.

Penalties

- Any person who contravenes any provision of the Act shall be punished with up to three years imprisonment or fine up to Rs. 25,000 rupees or both.

- However, according to the latest amendment to the 1972 Act enacted on August 2, 2022, which is yet to come into force, the fine was increased to one lakh rupees.

If the offence relates to animals under the first two Schedules, imprisonment can be between three to seven years, with or without a fine of Rs 10,000, which will increase to Rs. 25,000 after the 2022 Amendment.

What Are The Powers Of The State Government?

- It was in 1976, with the advent of the 42nd Amendment Act, that the subject of “Forests and Protection of Wild Animals and Birds” was transferred from State to Concurrent List.

- However, state governments still enjoy a host of powers under the WPA, 1972.

- The State government can appoint a Chief Wildlife Warden alongside wildlife wardens, honorary wildlife wardens, and other officers and employees.

- The state can constitute a State Board for Wild Life, consisting of the Chief Minister as chairperson, the Minister in charge of Forests and Wildlife as the vice chairperson, and at least three members of the State legislature, among others.

- State governments can also add or delete any entry to or from any Schedule or transfer any entry from one part of a Schedule to another, provided that any such alteration made by the State Government is done with the previous consent of the Centre

- State governments can notify certain rules, including the conditions subject to which any license or permit may be granted or under which the officers will be authorised to file cases in court.

2022 Amendment

To Download Monthly Current Affairs PDF Click here

Click here to get a free demo

Everything About CLAT 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

In which year did the The Wildlife Protection Act came into force in??

In the year 1972 The Wildlife Protection Act came into force .

Any person who contravenes any provision of the Act shall be punished for imprisonment for three years.

The Sarus crane falls under which schedule??

The Sarus crane falls under Schedule IV

“Forests and Protection of Wild Animals and Birds” falls under which list??

“Forests and Protection of Wild Animals and Birds” falls under Concurrent List

The Sarus crane is the state bird of which state??

The Sarus crane is the state bird of Uttar Pradesh.